Words of confinement

Not only having to reinvent their daily lives like everyone else, art dealers have also had to transform their habits and metamorphose their profession. Sales at half-mast, cancellations of all trade fairs, (difficult) adaptation to the digital world… among the pitfalls caused by this globalised isolation, the closure of the exhibition spaces was undoubtedly the strongest – and most symbolic – signal of the initial phase of the confinement. Many professionals could not picture themselves operating without them. Alain Lecomte tells us a nostalgic account of this dedication:

“First of all, this confinement made me realise that I was deeply attached to my venue, I missed it to the point where I was going to visit it on foot by walking the three kilometres early in the morning, around 5-6 o’clock, just for a few minutes and then return to our appartement. I encountered a science-fiction version of Paris, without cars, without pedestrians, empty of all life. I walked in the middle of the streets without a sound. The quai de Seine, the boulevard Saint-Germain… I must admit that my spirit sometimes took a hit, especially in the initial days.”

Home sweet home

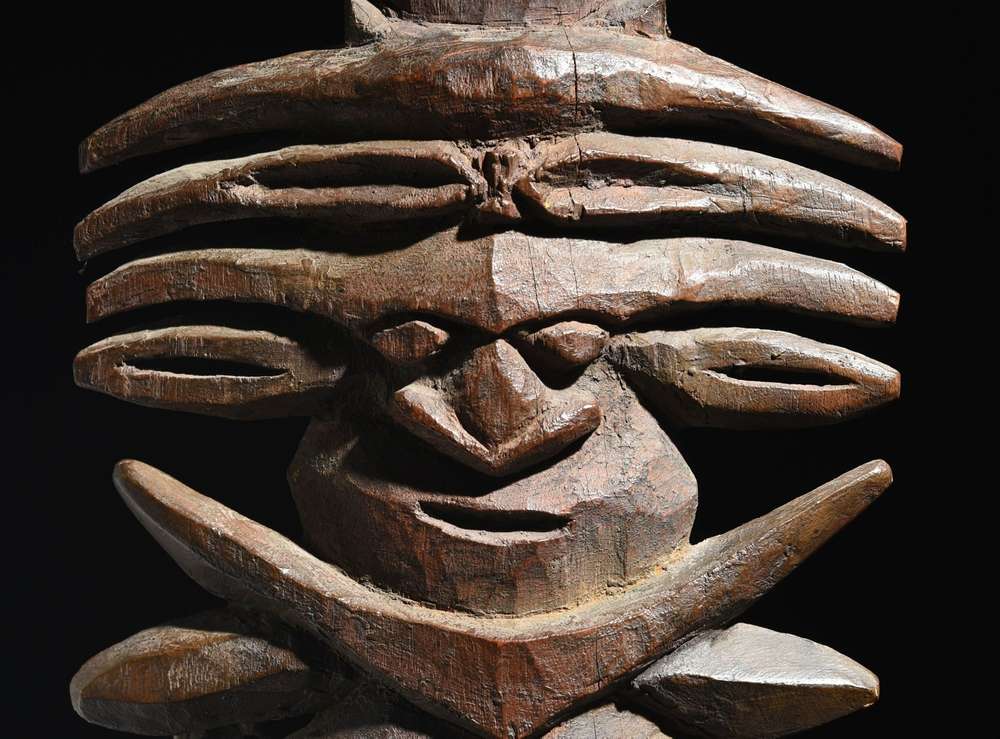

Admitting the relative comfort of his confinement, Anthony JP Meyer initially chose to spend this period at home before moving his office back to his Oceanian art gallery in the rue des Beaux Arts in the Saint-Germain-des-Prés district of Paris. “It was simply easier. I had the objects on hand, the documentation and most of the necessary equipment. Being an ‘employee’ of myself and having granted myself permission, I was able to escape during the confinement. I discovered Paris deserted under a magnificent weather. I was amazed to see so few people at the windows. Even on Saturdays and Sundays no one was sticking their heads out or enjoying the balconies.”

Then sideration gave way to organisation. For Alain Lecomte, whose gallery is also located in the rue des Beaux Arts, this means a radical change in his habits. “Step by step, we had to react. I continued to walk a lot early in the morning, but when I got home I started working on the computer. I took a lot of photos to post on Instagram – which takes up a lot of time (at least for me). We took part in Paris Tribal online, sent a considerable number of photos and proposals to our clients… At last I was alive again! Clients answered us, we discussed… It was the gallery without the gallery… But for the business, it is another story. I simply ended up not allowing myself to think about it.”

If for some closing their gallery was a wrench, for others it was the salutary occasion to self-question their profession. “The lesson I learned from this period is that it is possible to work differently without necessarily having an actual brick-and-mortal shop,” says Franck Marcelin, an expert in Oceanic art based in Aix-en-Provence. However, I missed three things: physical contact with my regular customers; the absence of my objects left in the gallery; my library of documentation.” For him, this unpredictable moment has above all confirmed his decision to move his gallery to his home at the end of 2021 “to welcome my collectors in a pleasant, more intimate setting and by appointment only.”

“The crisis has accentuated problems that were already latent."

“With hindsight, I tell myself that even if the Internet has undeniably taken an important place, the gallery still has a major role to play, whatever some might think,” says Alain Lecomte. “Where can you find a similar venue? Small museum where you can touch the objects; a setting for novices to learn and discover; a friendly place; a welcoming space; a meeting point for collectors… all of those at the same time. Our customers must come back in our galleries and now leave the Internet a little aside… to have the pleasure of return back to it at the next Covid," he adds not without mischief.

On top of the financial loss it represents, the closure of the spaces was not experienced as a tragedy by all. Some even saw it as a form of renewal, even liberation. “The crisis has accentuated problems that were already latent. The general trend is for the galleries to stop being physical meeting places with the public,” says Nicolas Rolland, a dealer specialising in the ancient cultures of sub-Saharan Africa and Oceania. “But if it is only to end up selling online, I feel it is a bit of a shame. People come less and less to the galleries. We will have to find a way to solve this problem.”

To decipher this disenchantment, already perceptible before the confinement, Anthony JP Meyer offers another form of explanation: “On the Internet, we encounter many buyers returning to the market when they were repelled by the snobbery of certain shops that had become too elitist. Mr. Smith, who has an interesting purchasing power below €10-15,000, but with astonishing regularity, had turned their back from the galleries. On the Internet, he does not face the redhibitory side of the merchant who evaluates his wallet as soon as he walks through the door. The Internet certainly does not humanise, but undoubtedly flattens out the rough edges.”

Let’s keep in touch?

For business where reliable interpersonal relations are key – and for which very often only trust between buyer and seller seals the acquisition – keeping the relationships and maintaining one’s networks are among the absolute priorities of professionals. For Swiss merchant Patrik Fröhlich, who describes a slightly less severe situation in Zurich where he is based than in France, the eight weeks of closure of his gallery will have been used to deploy a whole arsenal of dematerialised opportunity of contact. “We used this time to rethink our website and to keep in touch with our customers using all possible means (videoconferencing, telephone, email, etc.) Just after the confinement measures were removed – but with borders still closed – we reopened with an exhibition to welcome our local collectors. I can tell you that talking to passionate amateurs again after being alone in the shop for two months was an incredible feeling!”

Settled in his Provençal country house, Franck Marcelin also set about maintaining his relations: “My planning consisted of just two things: doing at home what we say that we will do ‘when we have time’ (and never end up doing) and keeping in touch with my clients. We did that by offering them new pieces as well as my latest acquisitions, using social networks – even if I am not very fond of this type of communication mode – such as Instagram and Facebook. Several sales were concluded in this way.”

Some, freshly converted to these new habits, intend to increase their online presence. Others, like Anthony JP Meyer, have discovered that they have the “soul of a blogger”. “I worked on texts, comments, reflections and published a series of seven or eight newsletters – one every single week," explains this specialist in Oceanian and Eskimo art. “I also did a lot of descriptions, object analysis, research, some sales and a few purchases. On Instagram, I published one small video every day. It was called One object a day keep the doctor away, a total of 17 films, every night at 8pm. It prove extremely popular and generated numerous requests for quotes on the pieces.”

Resilience and reflection

There was general consensus that some form of resilience allowed the sector to cushion the impact of the containment and slowdown of the art market. On a more personal note, many collectors and gallery owners will have capitalised on this unprecedented period to rethink their craft… and to get books, essays and other exhibitions out. “I’ve made progress on my research projects: I’m publishing two books, one of which will be officially released in September,” confides Christophe Hioco. “Everyone had more time and was more available. That was really the beneficial side of this period […] The secret is to take it positively. We cannot be here to moan and complain. We need to take this as an opportunity to take a step back, to consider what we can do better. »

Frédéric Rond, from Indian Heritage, is also working on a new book: “Confinement meant working only on photos and the Internet. For my part, I was at the gallery every day in absolute calm to work on my next book. “It’s almost a ‘blessing’ to be able to do research at home in peace,” says Serge Schoffel, a dealer in the Sablon district of Brussels. “I also found some beautiful objects and managed to sell several pieces. I had quite a lot of contact with regular customers and even with new ones. In spite of everything, business still went rather well. Things happened naturally.”

"The secret is to take it positively."

This time of reflection away from the exhibition spaces also led Nicolas Rolland towards writing: “It allowed me to get back to working on subjects that had been on hold for a long time. I opened my gallery only a year and a half ago and was therefore entirely devoted to that. With the confinement, I was able to get back to my editorial and research projects. In particular, I’m making progress on a text that I left aside for too long… even though I’m still clearing the ground on that.”

In the wake of this, other initiatives are flourishing. “We have developed a new idea, which we have called ‘7 à la maison’, where we bring together seven quality merchants at a friend’s house,” explains Laurent Dodier. “It is a sort of mini-fair with seven fellow exhibitors. The first edition will take place on the last weekend of September.” “But even with all this extra time, there are still many things I would have liked to do and haven’t managed to“, regrets Anthony JP Meyer. “Just not enough time. I’ve written a lot, thought a lot, published a lot. As the Internet is our only means of communication with the rest of the world, I have used it to the best of my knowledge.”

No escape from fairs?

But for those who work mainly at trade fairs, the situation is tricky. This is the case of Laurent Dodier who notes that “all fairs have been cancelled except for the Parcours des mondes, which is coming back in a reduced format, but Paris Tribal, the Rare Book Fair, the Burgundy Tribal Show, the Biennale… all had to close.”

While he had left to confine himself in Brittany in an isolated corner with risky Internet connections, Nicolas Rolland had to resolve to the abortion of the 2020 edition of Paris Tribal. “Paris Tribal could just not be a digital event. It did not make sense and in any case the website did not allow for something like this. We had no choice but to cancel. Also, without a good Internet connection, it was really difficult to develop relevant things online. Nevertheless, the impact of Covid must be put into perspective; the question of pushing our job in the digital space was already there. All the merchants were already wondering about it.”

Some dealers managed to slip through the net. “As far as the events that concern me, I did rather well: the confinement took place right after the BRAFA and the Parcours is maintained,” says Serge Schoffel. “At the beginning of the crisis, I have to admit I was a bit worried, but things are going quite well for me and the dynamics are generally positive, so I admit I am rather happy. I made two online catalogues, something I do not usually do, but since I did not have a choice, I went for it… and it worked well! It makes me want to repeat the experience!”

“It was in fact nothing less than a never-ending race forward."

Anthony JP Meyer analyses that the situation – which became explosive with Covid – had already been simmering for several years. “The system meant that we made the principal of our turnover during fairs rather than at home in the gallery. We all felt that there was an overflow of events, but no one really knew how to get out of it. Stopping one’s participation implied the negative image of someone who was dropping out of the circuit. Therefore, everyone just continued to participate in these events. “It was in fact nothing less than a never-ending race forward. Moreover, the fairs were performing less and less.”

According to him, for a “small” gallery like his, the annual budget for fairs is around €500-600,000. The absence of these events quickly becomes a substantial saving… but also a loss of income that he says he is trying to make up for by being “flexible, innovative, courageous, resilient and acrobatic.” In the future, will merchants be more selective in their participation in shows? “The lesson I have learned from this period is that one should always have to keep close eyes on costs. This is extremely important, vital even,” says Adrian Schlag, a primitive art gallery owner based near the Sablon in Brussels. “If you have to do expensive fairs, you should now ask yourself at least two or three times whether it is the right choice.”

Lessons of crisis

By refocusing on investment strategies, many dealers have already put a mental end to this year, which they consider to be white, hoping for some form of recovery for 2021. “I am convinced that objects will arrive on the market in the coming months. Some professionals will need cash, but they are still waiting as much as they can”, deciphers gallery owner Christophe Hioco, this former banker from JP Morgan leaning however towards the greatest caution. “Crises come back regularly. What is special about this one is that eight months after it began, we still have no idea what the future will bring. In the case of the subprime crisis for example, we knew from the outset that it was a question of time, the Fed and the different states were making decisions and taking actions. As for Covid, we simply do not know, it is a new phenomenon.”

“At the same time, I see the auction houses that continue to perform very well. This shows that there is a lot of demand,” continues Anthony JP Meyer. “It might just be a sabbatical year that will prove to be beneficial for the market. There were too many gallery owners, too many objects. Prices had become the only thing that mattered. This allows a kind of ‘rebalancing’, a re-framing of the ecosystem. Well, that is what I foresee… time will tell!”

"There are no more hidden or secret objects."

It could be that the change might also be sociological. “Collectors and amateurs have remained active and vigilant […]. I believe that a new clientele is emerging because of home confinement and all the increased leisure time, which is positive for the art market,” observes Belgian dealer Martin Doustar.

While some dealers are confident that they have not suffered too much from the health crisis, all are waiting for a rebound. “For exceptional pieces, you have to be attentive,” says Belgian gallery owner Adrian Schlag. “The middle-market is gradually disappearing; it is in any case more difficult than before. It is also much harder to find great opportunities. Everybody now looks at everything everywhere, even on small vacations in England or Germany. There are no more hidden or secret objects. In any case, much less than in the past.” A phenomenon that has been amplified by the shift in sales towards the Internet. “The web can bring some happy surprises, but also more bitter discoveries,” summarises Anthony JP Meyer. “Many collectors will certainly feel some discomfort for having bought more or less genuine, more or less well-described, more or less interesting ‘stuffs’… that they – thinking they were getting a good deal – finally paid way too much for…”